Steven R. Dowell, Alexandria, Kentucky

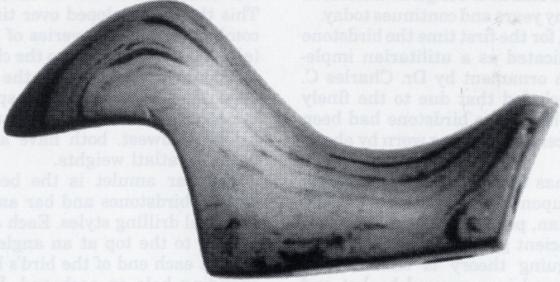

“Looking over the fence” form birdstone. Found in St. Clair County, Michigan. It is 4 inches long and 2 1/8 inches tall. Pictured on page 521 of Birdstones of the North American Indian, Ex J. Ringeisen, Dr. T. H. Young, and J. Gentry collections. Now in the collection of Charlie Wagers.

Recently I had the pleasure of assisting a good friend and fellow collector in the acquisition of a birdstone. It was not just any bird either. It is fabulous in design, material and provenance. This particular piece once belonged to the late Dr. Gordon Meuser, the Columbus, Ohio, collector who is remembered for his large collection of slate and stone artifacts. It was pictured in Birdstones of the North American Indian while in Dr. Meuser’s collection and was ultimately given to the late Max Shipley as a Christmas gift in 1969. In fact, on the bottom of the bird, in Meuser’s handwriting, is the notation, “To Max, Merry Xmas 1969. G.F. Meuser.”

As I sat there, bird in hand, I could not help but to marvel at it. When it came time for it to leave my office and begin its flight back to Ohio, I did not want to let it go. It was like having to tell a loved one goodbye. And to be quite honest, I could not at the time put my finger on the reason I was so enamored. True, the banded slate it is made of is beautiful. True, the symmetry is outstanding, and true, the history behind it would stagger the mind of any collector interested in the history of this fine hobby of ours.

However, as I was walking back to my office thinking of the rare form that I had just let go of, it hit me. It was the rarity of the piece. More specifically, I was intrigued by the rarity and the mystery behind each and every birdstone that I have ever had the privilege of holding or owning. That was it. The mystery of, in my humble opinion, one of the most interesting artifacts ever left behind by early North American man generates the extreme interest I have in birdstones.

Later that day, I found myself at home examining my best birdstone (Vol 44 #4 Pg 193 CSAJ). As my thoughts drifted, I kept asking myself what they were used for. Why was such great care exercised in their manufacture and even repair? And perhaps most importantly, why are they so incredibly rare?

To answer the first question, one need only go to the undisputed “professor” of birdstones, none other than Earl C. Townsend, Jr. Mr. Townsend, at great personal expense, published the “birdstone bible,” Birdstones of the North American Indian, in 1959. This book has only one rival in comprehensiveness, that being the bannerstone book published by Byron Knoblock several years earlier. Only seven hundred copies of Townsend’s book was printed. The natural result is that his book is in itself as collectible as a good birdstone . . . if you can find one available for sale.

The first literary mention of the birdstone may well be in an essay by one Thomas Hariot. Hariot, sent to what is now Virginia by Sir Walter Raleigh from 1585 to 1587, wrote of his encounters during this trip. This was published as A brief and true report of the new found land of Virginia in 1588. Included with this work were several engravings by John White. White, also a colonist in Hariot’s time, made numerous watercolors and drawings of Indian life and customs of the area. One of the most pertinent engravings by White is one that depicts a man or sorcerer wearing a stuffed bird with extended wings on the right side of his head. The idea was that the bird effigy allowed the sorcerer to leave the earth and enter a higher level where he would communicate with the gods.

According to Townsend, the first discovery of a birdstone by a Caucasian was probably in 1840. “Students of the old Theological Institute then located at East Windsor Hill, Connecticut, discovered a fine birdstone and a soapstone dish of about one pint capacity along with several other articles in a burial at the west end of the institute grounds on the bank of the Connecticut River.”

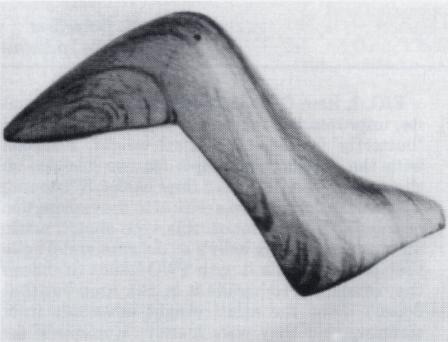

Genesee County, Michigan birdstone. It is 3 5/8 inches long and 1 3/4 inches high. Ex. Dr. T. H. Young, J. Gentry and was featured on page 491 ofBirdstones of North America. Charlie Wagers collection.

From the very beginning, the use of this enigmatic artifact has been elusive. Many have advanced various theories ranging from the use of the birdstone as a device to aid in the husking of corn to maternity charms or emblems used to aid in child conception and birth. As with most conclusions regarding antiquities and their method of manufacture or use, there is a method that should be followed. First, the hypothesis, an educated theory. Then the search for evidence in support of the theory is an absolute. The use of the birdstone is no exception. It should be noted, however, that living members of various Indian tribes provided no useful data. As Townsend puts it, “It is now quite certain that birdstones were not in use for any of their intended purposes during the lifetime of any aged Indian known to Gillman, and the theories advanced as to uses of birdstones by several other ‘aged Indians’ are so different as to show that the conjectures were made without any reliable bases.”

Nevertheless, early on, in the mid 1800s, Squire and Davis concluded that the birdstone was used as charms or badges of distinction having a connection with the religious rites of prehistoric aborginials. Charles C. Jones in his Antiquities of the Southern Indians, published in 1873, followed that line of thinking. The charm or religious affiliation belief lasted for many years and continues today.

However, in 1875, for the first time the birdstone was seriously implicated as a utilitarian implement as well as an ornament by Dr. Charles C. Abbott. Abbott concluded that due to the finely drilled suspension holes, the birdstone had been an integral part of certain clothing worn by aborginal women.

In 1888 Dr. Thomas Wilson of the Smithsonian Institution, acting upon information from a transient Chippewa Indian, postulated that birdstones were used in an ancient gaming device. The idea behind this intriguing theory is that several birdstones were placed in a covered basket and shook and various persons would attempt to guess how many would be left standing when the basket was opened. It was thought that bets were made before the opening. While romantic, this theory is quickly discounted by those who have ever handled a good number of authentic birdstones, as many authentic birdstone cannot stand on their own accord. Most are top heavy and tend to fall forward, and many of the bases are convex or slightly rounded, preventing them from free standing. Mine, for example, is no exception.

Then came Warren Moorehead and his publications The Birdstone Ceremonial (1899) and a year later Prehistoric Implements (1900). In those publications, Moorehead suggested that the plain, saddle or bar birdstone, without pop-eyes, were worn on the heads of women about to be married, while the more elaborate pop-eye types were used by shamans or sorcerers as luck charms. In The Birdstone Ceremonial Moorehead provided room to Professor Frank Cushing to advance his theory of birdstone usage. Cushing opined that birdstones were placed upon the top of gorgets and fastened to them by ties through their holes. Many years later, Moorehead would reject this idea.

Another use for birdstones theorized by pioneering American archaeologists was that these curiously beautiful stones were part and parcel of atlatls. Specifically, it is thought that they may have been akin to the bannerstone, now confirmed as atlatl weights through W S. Webb’s efforts at the Indian Knoll Site in Ohio County, Kentucky. This theory developed over time as a result of a combination of discoveries of bird-shaped stones (albeit nothing similar to the classic shapes collectors know) in dry caves in the Southwest and the close similarities certain aspects of birdstones have to boatstones and bar amulets that are found in the Midwest. both have also been linked to usage as atlatl weights.

The bar amulet is the best example. When drilled, birdstones and bar amulets each exhibit identical drilling styles. Each are drilled from the bottom to the top at an angle so that there is a hole at each end of the bird’s bottom and a corresponding hole on each end. Perhaps even more importantly, a classically shaped bar amulet reminds one of two rear portions of birdstones that have been connected. This conclusively places bar amulets and birdstones within the same family — cousins, if you will.

The atlatl weight theory comes into focus as a result of certain observations by Guernsey, Kidder and Prof. J.T. Patterson centering on the fact that a small number of bar amulets and birdstones have a small groove or “scooped out area” cut between the holes on the bottom. It is thought that this facilitated attachment to the atlatl. However, I agree with Townsend that the miniscule number of such specimens in relation to the total number of known examples cannot be relied upon as proof positive of such a old assertion. Further, given the fact that birdstones and bar amulets co-existed, particularly during the Glacial Kame era, it is hard for me to believe that the two artifact forms evolved from one to another. Additionally, the birdstone does not have a large central hole or attachment grooves. Rather, the attachment process for birdstones is through small, usually less than 1/8 inch diameter, perforations described above. Logically, this minor attachment process is not conducive to the heavy use to which an atlatl would be subjected. Therefore, this use as an atlatl weight is highly speculative and not based upon evidence.

Townsend, on the other hand, firmly believes that birdstones were used as handles for the atlatl. He bases this opinion on discoveries of Peruvian atlatls having bird-shaped objects fastened to the proximal (handle) ends where they functioned as grips. Townsend continues that the shape of the elongated slate birdstone and the fact that many birdstones exhibit broken perforations “that could have been caused by the tugging and snapping of the atlatl shaft” is further evidence in support of this theorized use. Perhaps one of the most compelling pieces of proof for this use lies in the confines of common sense. Townsend states, “Most finished birdstones ‘feel good’ in the hand, as if they were made to be fitted therein.” When one examines closely the illustrations set forth by Townsend in support of this theory, its plausibility becomes evident.

Since the publication of Townsend’s book, little supported work has been offered from either the professional or the avocational side of archaeology or anthropology as to the origins and uses of birdstones. Some writers have made attempts, however. For example, in the early 1980’s Glenval Fincham posed the theory that birdstones were effigy duck decoys. This position was based upon several points of interest. First, prehistoric man in North America developed and utilized the effigy concept. This fact cannot be ignored. Most often, the image was highly stylized, bringing out one, maybe two, particular attributes the artist sought to portray or establish. Additionally, some prehistoric inhabitants manufactured and used decoys. Fincham asserts that examples of these have been found in dry caves in the Southwest dating back to early Archaic times. These artifacts, made of wood and twisted fibers, were doubtless covered with the skin and feathers of water fowl.

A third piece of evidence asserted by Fincham is the fact that certain prehistoric cultures in North America were expert wood carvers. Wooden masks excavated from the Spiro Mounds in Oklahoma and Key Marco, Florida, attest to this fact. Of particular interest is Fincham’s assertion that another piece of proof for his theory is the fact that the distribution patterns of authentic birdstones correspond to the areas drained by the Great Lakes, not including Lake Superior. Recall that Townsend places nearly 85% of all birdstones being found in this area. This same area is known for the vast amount of water fowl present when North America was first being explored by the Spanish. It does not require a large stretch of imagination to envision prehistoric man being blessed with the same abundance of food.

Finally, Fincham combines the above facts with his own personal observations that no birdstones of which he was aware displayed feet, legs or wings. Rather, the vast majority of birdstones resembles an aquatic bird sitting on the water.

Fincham’s theory is probable and seems to be supported by some logical evidence. However, there is a major flaw in his reasoning. There have been a huge number of birdstones discovered that do exhibit feet. Most notably, the pop-eyed variety usually has a set of dual ridges on the bottom upon which the piece rests. Clearly, these are feet.

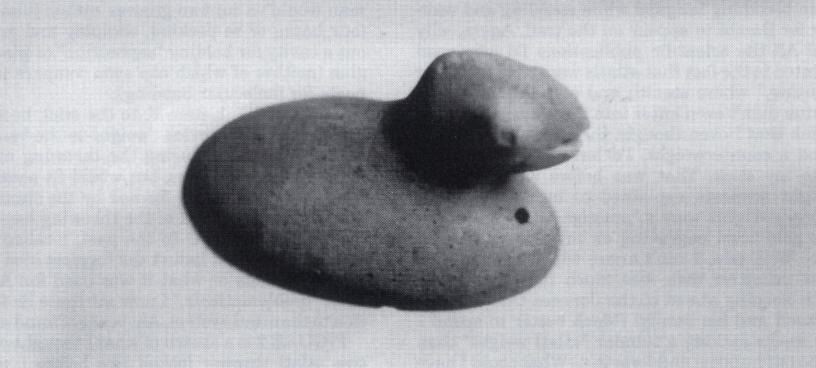

Birdstone found in Attich, Ohio. It is 4 inches long and 2 inches tall. Ex. Joseph Roe collection. From the collection of Charlie Wagers.

A salvaged bird from Van Buren County, Michigan. It is 2 1/2 inches long and 2 inches tall. It was also featured in Birdstones of the North American Indian, Ex Cameron Parks collection. From the collection of Charlie Wagers.

Indeed, some birdstones actually resemble dogs and have been connected with canine effigies.

The distribution of birdstones is immense. Townsend opines that while birdstones were used all along the eastern seaboard and as far north as Nova Scotia, they were not transported beyond the Mississippi River. He bases this contention on the fact that while there have been a few reports of birdstones being found in Arkansas and Minnesota, their history cannot be substantiated. However, since Townsend’s statement on this point, at least one birdstone pre-form with a traceable history has been reported from Minnesota. While there have been scattered reports of birdstones being found from Kentucky to Maine, the areas of the heaviest concentrations of birdstone discoveries is located from southeast Wisconsin, eastward through northern and central Indiana, through northwest and north-central Ohio, to southern Ontario and southwest New York.

My belief as to the primary use of birdstones mirrors that of Converse. He says it best: Not wishing to add to the numerous theories surrounding the birdstone, it should be sufficent to say that in the absence of conclusive evidence of their function, logic points to their use as ornaments rather than utilitarian objects. They are more likely representations of the bird, which is an apparently important motif as exemplified by the two engraved sandal-sole gorgets protraying birds.

After more than one hundred years of investigation and postulation, the origin and use of the birdstone still eludes a definitive answer. In reality, the answer to this, and any other question, lies with the exercise of common sense.

Bust birdstone from Greenup County, Kentucky. From the collection of Charlie Wagers, Fairfield, Ohio. It is 2 1/2 inches long and 1 1/2 inches tall.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Townsend, Earl C., Jr.

1959 Birdstones of the North American Indian, privately published, Indianapolis, Indiana.

Mangold, Bill

“Birdstone or Dog Effigy,” Central States Archaeological Journal, Vol. 20, No. 4, Pg. 146-148.

Parks, Cameron W

“A Novel Theory on the Use of the Birdstone,” Central

States Archaeological Journal, Vol. 17, No. 4, Pg. 148-155.

Dowell, Steven R.

An Unusual Birdstone Form: Possible Theories of Its Use and Development,” Central States Archaeological Journal, Vol. 37, No. 2, Pg 85-87.

Smith, John C.

“A Minnesota Birdstone,” Central States Archaeological Journal, Vol. 41, No. 3, Pg. 114-115.

Converse, Robert N.

1979 The Glacial Kame Indians, Special publication of the Archeological Society of Ohio.

Converse, Robert N.

1978 Ohio Slate Types, Special publication of the Archeological Society of Ohio.