Walter Williams, Eastland, Texas

I have often noticed as guests come into my house and observe a few artifacts that are displayed, how they usually comment on my “nice collection” and then begin to tell about a relative that also has a collection. They display a passing interest and then we move on to the purpose of the visit. On the other hand, let a fellow collector observe the same displayed artifacts and he wants to talk in detail about particular pieces. The collector is not content to just observe, but will want to open the case—inspect, touch, even smell the artifact. The avocational archeologist has an intrinsic interest in knowing who, what, when, where and why the artifact was manufactured. Due to the number of avocational and professional archeologists and their intrinsic curiosity, few artifacts maintain their mystery for long. One of the exceptions is a ground stone artifact commonly referred to as the Waco Sinker.

One of the earliest papers on this unique artifact (Watt, 1938), referred to them as Waco Sinkers because they were initially found in a very limited area adjacent to the Brazos River near Waco, Texas. Because this area was once the home of the Tawakoni, later called Wacoes, and because the relic also looks somewhat similar to modern day fishing sinkers, the name stuck. Also worth noting is that Watt made the connection that the Wacoe people were not necessarily the makers of the artifact by stating, “some sinker camps are not Tawakoni sites and some Tawakoni sites are not sinker camps.” The Sinkers are often found in camps; one camp noted by H. G. Moore in 1935 yielded 536 examples (Moore, 1935).

Time and additional discoveries have shown that the distribution of Waco Sinkers is much greater than originally thought, some being found as far south as Atascosa and McMullen Counties (McReynolds, 1981). They have also been found close to the border with Mexico in Dimmit and Willacy Counties (Hester et al, 1978).

Coastal waterways are of increasing interest to archaeologists because of the number of Early Man sites being discovered and the cultural clues left in stone by the people that lived in these areas. The McFaddin Beach site washed out large numbers of Paleo points, most notably both Eastern and Western Clovis type points. Plummets and Waco Sinkers have also been found eroding from the beach. This would tend to indicate a very early age for the Waco Sinker, quite possibly Paleo. The Gault Site is known for the “absolutely consistent stratigraphic sequence.” Of particular note is a zone with nothing but early Archaic artifacts, specifically Clear Fork tools, Angostura, Hoxie and, of course, the Waco Sinker. Watt noted that “The absence of pottery or sherds in the sinker camps… places them definitely in a pre-pottery horizon.” The Wilson-Leonard site in Williamson County, which would be considered part of the core area of distribution, Carbon 14 dated four examples at 9650-8000 B.P. and was associated with Golondrina and Plainview points (Dial et al. 1994). Certainly, the Waco Sinker was an important tool for people who were making the transition from a purely migratory lifestyle to a more settled or seasonal one.

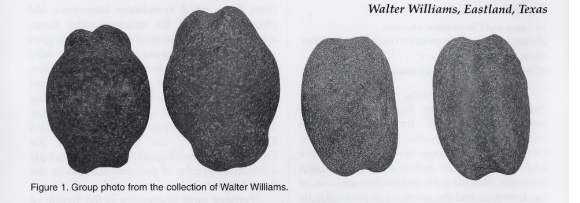

Some examples are rather simple in manufacture. Others required many hours of pecking, grinding and polishing to obtain a finished tool (see first and second from left, in figure 1). The enigma surrounding the Waco Sinker is determining purpose. For many years, the sinker idea dominated because initially, they were found close to water. The problem is, most Indian camps are also found near water. So, one could easily place too much emphasis on a fishing use. In addition, if used as fishing line weights or fastened to nets, more Waco Sinkers should be found in riverbeds and creeks.

A bolo concept has more recently been accepted. The Poverty Point site in Louisiana has provided many examples of plummets that are broken in the field and brought back to camp where the drilled ends were regularly replaced. Used for waterfowl, it is believed the plummets were part of a bolo rig. The five stone rig was very effective, and the transition from drilled to notched stones was a geographic and material modification. Since hunting was a lifetime skill and the same tools were often used for years or until they broke, great pride was often taken in their manufacture. According to Russell Long, “Because of the amount of work involved on the ‘sinker,’ it is difficult to imagine any use other than a personalized Bolo.” (Long, 1977)

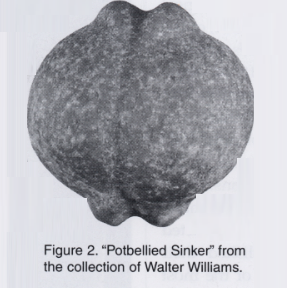

Some have suggested use as a charm for the more notable examples, but this seems unlikely because of their frequency, spatial patterning, and the fact that they have not been found in burials. Many are isolated finds on flat surfaces of the Blackland Prairie. This would suggest they were lost individually, which could indicate use in a net, but a land net rather than a fishing tool. Originally, it was believed that the sinkers with notches all the way around the artifacts were bolos, the examples with notched ends, but not around the entire artifact, were used on nets. Today, several “Potbellied Sinkers” have been found that are both notched on the ends and grooved all the way around the artifact. This might indicate a use in either manner depending upon the need on a particular day (see figure 2). Robert Talley, a Texas collector, believes hunting groups would come together, each bringing a net that was then fashioned together forming a very long tool that could stretch a couple hundred yards. Controlled fires or animal drives forced the animals into the nets placed in strategic locations. The sinkers maintained the net near the ground after the animal was entangled. After the kill, the nets were then returned to the family groups and to facilitate transportation, the sinkers were removed from the nets.

Avocational collectors must always keep in mind that the environment today, may not be what was prevalent at a given point in the past. The climate 9000 B.. in Central Texas was more similar to what Kansas is like today. The Brazos River would not have been cut as deeply and would have been much broader than at present, creating a short-grass, wetland environment that provided the possibility for the exploitation of riverine fauna (Waters and Nordt, 1995).

Waco Sinkers are usually more or less the same weight and size. This leads some to believe they were used as part of a hunting tool at the end of the Holocene to trap a particular type of animal. When the animal disappeared with the changing environment and possibly becuase of excessive hunting practices, so did the need for the Wako Sinker. This would explain why, at least in some areas, they disappear from the archaeological record about 7000 years ago. The Waco Sinker is an enigma, perplexing but captivating. We will probably never have all of the answers, but each documented example allows us to ask the right questions which will finally and ultimately lead to a better understanding of this wonderful Texas relic.