by Mike Sutton, Harrisburg, Illinois

Originally Published in the Central States Archaeological Journal, Vol.56, No.4, pg.200

Originally Published in the Central States Archaeological Journal, Vol.57, No.2, pg.74

When moons and planets synchronize into alignment, karma can peer over a collector’s shoulder and smile. Something extraordinary may be seeking a long tenure in his cabinet.

Premium artifacts with solid documentation are quite elusive.and opportunities to acquire can be rare. If a serious collector gets the chance to secure a genuine, recently discovered, top shelf piece for his collection, he should make the deal and record every bit of information on the artifact he can possibly obtain. It’s an important and critical imperative for all interested in preserving the past.

An unlikely person instilled this belief in me. A local rock hunter had made the “find of a life-time” when he discovered an exquisite Ramey knife just east of the small village of Cypress, in southern Illinois. He was a tenacious surface hunter, but bass fishing was his first love. He decided he needed a new bass boat, so he decided to part with the blade. I considered the piece to be an important example of southern Illinois lithic art, and desperately wanted it. But it was the mid 1980’s, the country was just coming out of a recession, and the blade was beyond reach for me, or so I thought.

To my delight, after a chance mention to my parents, my mother made a gesture that numbed me. I was instructed to buy the blade with her money, and pay it back as I could afford it, in monthly instal ments. Surprisingly, she didn’t think I was insane for spending that kind of money on a rock, but she understood the potential for a priceless heritage.

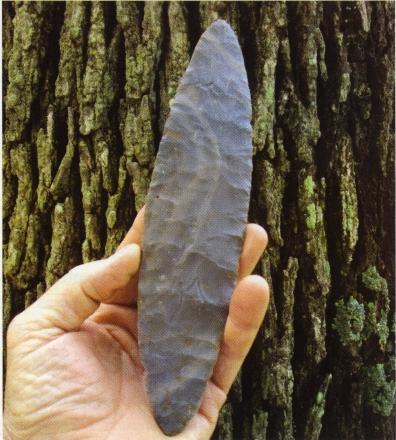

Indeed, I was now the proud new caretaker of the flawless Johnson County Ramey knife, appropriately wrought from heat-treated Mill Creek chert. I frequently pulled the rock from its place of safe keeping, and meticulously examined it, to assure myself that I actually owned the thing. Yes, it wasn’t just a fantastic dream, I had really acquired the blade, and oh, what a fine and perfect specimen it was. A mother knew precisely what a son’s novice collection needed.

Several months passed, and one Sunday in August in the late 1980’s, I attended the summer rock-show at the Executive Inn in Owensboro,Kentucky. As I entered, remarkable thing was happening. A noticeably excited, but small band of people were working their way around the room; stopping to chat, gaining and losing members as it meandered around the expansive room’s perimeter. Eventually, as I continued to visit with fellow collectors and displayers, I made my way closer and closer to the group to see what was causing all the fuss.

Three collectors from Crittenden Co., Ky., were commanding all the attention. As I came to within a few feet of the commotion, I noticed that the leader of the clan was pulling something from an old, wrinkled, paper sack to the thrill and elation of everyone that huddled around. As my curiosity morphed into anxiety, I continued to chat with a friend, while paying close attention from the corner of one eye. In and out, the mysterious article would flash to the sounds of approval as the group leader would permit brief glances to those who wanted a peek.

Then at long last, as the men ever so slowly approached, I made eye contact with the one who held the tattered bag. With an inquisitive glance, I raised my eyebrows as if to ask? “Can I see?” Without hesitation he pulled his treasure just half way from the bag as if it might escape when fully exposed.

For the next few seconds, I peered at one of the most striking examples of lithic art I had ever seen. Protruding from the old sack was a drop dead, killer of a hornstone blade that was so superb, it literally took my breath. Although the paper bag concealed its lower half, the piece looked to be a foot long. Its dark blue-gray flint and bi-pointed profile was not unlike the Benton blades from northern Mississippi that have been found in caches and associated with turkeytails. Its most, notable feature was the elongated, concentric banding that rippled through the blade’s matrix and curved across its face. The sheer beauty of the material, coupled with the excitement of the moment, seared the experience into my mind. As the years pass, I will have the luxury of revisiting the memory again and again, as it was a thrilling moment in time I will not soon forget.

Even today, thinking back to that very afternoon, the image of the blade and the wrinkly bag is still vivid in my head. The contrasting images are paradoxical, indeed! I was struck by the profound influence material can play in the perception and the reality of aesthetics. I found it hard to comprehend that the blade in the sack had been crafted from the beautifully exquisite material. The nodule it was made from must have been enormous and quite valuable.

That day at Owensboro, those sharing the blade had an impressive story to tell. The men had uncovered their extraordinary find the day before that very Sunday. Swollen with pride, they were compelled to show it off to anyone who would share their excitement, and Owensboro was the perfect venue to exhibit the trophy.

According to the blade’s owner, it had been uncovered in the deep back woods of Crittenden County Kentucky, somewhere between Marion and Tolu and in close proximity to the Ohio River. Without a doubt, it was a huge piece of finely worked flint.The excitement they must have felt, as the rock was uncovered is an emotion all artifact hunters relish, but few experience. A pristine blade that had lain undisturbed for thousands of years. It would become an object of adoration for all who experienced it.

A couple of years later, I learned that Chalmer Lynch, the old time collector/dealer of Evansville, Indiana fame, had purchased the remarkable find shortly after my encounter at the Kentucky. Show. In 1990, Chalmer was fast approaching one hundred years of age, and one by one, the old gentleman was selling off the cream of his personal collection. The instant I learned that the blade was for sale, I contacted the Mr. Lynch to tell him I was interested, but was informed that I may have called too late. Another collector had tried to acquire the piece, but didn’t have quite enough cash to close the deal. Chalmer wouldn’t take the guy’s shotgun to make up the difference. I was told that the guy had two weeks to come up with the money, and if he didn’t, the blade was mine.

He didn’t, and fourteen days later this lithic masterpiece was crossing the Wabash to its new home in Illinois.”Used by Permission of the Author”

To learn more about or to join the Central States Archaeological Society, click here:CSASI.org