Toney Aid, West Plains, Missouri

Take an ungrooved celt, polish it, stretch it (up to two feet long), flare the bit slightly and what have you got? A long-stemmed spud! For many years archaeologists for reasons of clarity have wished that the spud might be renamed “elongated celts” or “sociotechnic axe form,” but the common name of “spud” persists, named for a type of spade used to dig potatoes. Early archaeologists thought the spud was some type of digging tool. Clarence B. Moore (Moore 1903) was one of the first to describe it as an unusual form of celt, not an implement meant for digging. Very few long-stemmed spuds have chips or show any evidence of wear on their bits which would indicate use in digging or chopping.

Archaeologists now recognize that spuds are ritual axes used in Mississippian society as political or religious symbols during ritual ceremonies. James B. Griffin, writing about spuds found at Spiro (Griffin 1952), stated, “Polished, long handled stone spuds are commonly found in sites where other artifacts indicate a connection to the Middle Mississippian Southern Cult. The spud has never been found as a part of any Hopewell culture at any site. It is a clear time marker for the post-Hopewell Mississippi levels.” Since that time the spud has been recognized by several writers as one of the symbols used in the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex. James A. Brown, in his most recent study of Spiro (Brown 1996), says, “Although sociotechnic weapons are too delicate or too cumbersome for use they are neither ‘useless’ or merely ‘decorative.’ We can attribute to them great importance as social and moral symbols due to their capacity to evoke the power to make them possible.” J.V. Knight calls them “sacra,” suggesting artifacts that are charged with supernatural meaning in the context of ritual activity or display (Knight 1986: Emerson 1996).

Spuds have been found in at least ten states. They are usually associated with Mississippian burials dating before about 1350AD. The majority of them are made from greenstone, a material found mainly in the Tennessee-Cumberland river drainage areas. Perino and others have stated that these implements were most likely manufactured there and traded to other locations (Perino 1964). They have been found in Florida, as far west as Spiro, and as far north as the American Bottoms that surround Cahokia.

How were spuds used in ceremonies? There is ample evidence that they were hafted, much as common axes, but with more elaborate handles. Spuds found at Spiro and by Moore in Arkansas, as well as two examples discussed following, all show stains on their polls that indicate they once had handles. A portion of an engraved conch shell found at Spiro (Phillips and Born 1980: Plate 204A) shows a hafted spud in the belt of a dancing bird man. This spud is hafted in a handle similar to the woodpecker handles found on copper celts end of the celt entering the back of the head of a woodpecker and coming out of the mouth, like a tongue between the open beak of the bird. A spud that size in an elaborate carved wooden handle would have been very impressive.

A Tale of Two Spuds

John Sutter (1856-1941) was an early collector of artifacts from the American Bottoms area across the Mississippi River from St. Louis. He lived in Edwardsville, Illinois, where he was the editor of the local newspaper and later a real-estate and insurance salesman. Sutter collected a large assortment of artifacts from the American Bottoms. According to his daughter-in-law, he “acquired most of his collection from the Thomas T. Ramey family.” The Ramey family owned the land Monks Mound stands on at Cahokia from 1868 through July of 1925. Emerson, in an article

on this spud and an associated pipe (Emerson, 1996), notes, “While Sutter did not record provenience on these items…and it is possible he limited his collection to the general American Bottoms locality…and this raises the interesting possibility that the spud…may have been recovered from the Cahokia site.” Four spuds are known to have come from the American bottoms. Perino reported two from the central area of the Cahokia site, while Pauketat wrote about one more from the Soucy Cemetery in the present-day village of Cahokia (Pauketat, 1983). After Sutter’s death the majority of his collection was donated to the Madison County Historical Museum. A few of his most important items, including the spud and pipe, were kept by the family and later dispersed.

Another spud found in Arkansas a few years before the Sutter piece, the Thibault Spud, also has an interesting story. The Thibault spud was found by J. K. Thibault in the mounds on his property prior to 1883. In that year, Edward Palmer, working for the Mound Exploration Division of the Smithsonian’s Bureau of Ethnology, was in Arkansas surveying mounds and collecting artifacts (Jeter, 1990). During his travels Palmer visited J. K. Thibault at his home along the Arkansas River, southeast of Little Rock in Pulaski County. In Palmer’s journal he records that during the visit Thibault donated fourteen fine specimens of pottery and four crania from his diggings in the mounds on his property. “The gentleman presented me with several specimens for the National Museum. He has some rare painted specimens of pottery and some with curious inlaid ornamentations. He has also some curiously shaped specimens of pottery and some pipes, shell beads, the finest ever seen by me, and a curious paddle shaped implement made of slate.” (Jeter, 285-6). Although Palmer wanted the paddle-shaped implement, Thibault declined to give it up and kept it in his private collection. Later it passed to one of his daughters, who married F. T. Gibson of Little Rock. The Thibault Spud remained in the Gibson family for a hundred years.

Both the Sutter and Thibault spuds are interesting examples of Mississippian ceremonial artifacts. They are two more pieces to fit in the puzzle of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, helping us to understand a little more of that culture.

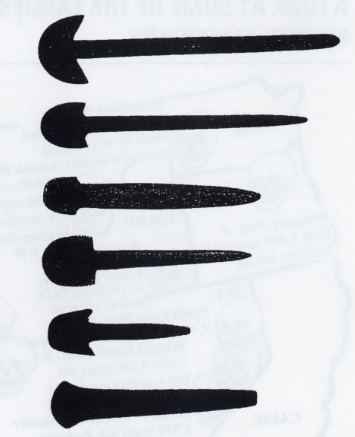

Silhouettes of some of the more famous spuds from top down: spud from Spiro Mound in LeFlore County, Oklahoma; The “Grove Spud,” from St. Clair County, Illinois, the Sutter spud from the American Bottoms in Illinois; the Spiro Mounds spud from LaFore County, Oklahoma; the Soucy Cemetery Site spud, from St. Clair County, Illinois; and the Thibault Spud from Pulaski County, Arkansas. Graphic by Roy Hathcock.