Matt Rowe, Oklahoma

Ancient ceramics are a wonderful way to add spice to any artifact display. While stone items are still the number one collectible, no collection is complete without pottery. Earthenware vessels used to be an easily acquired commodity, available for a moderate price. Due to strict laws, availability, and increasing market demand, they are becoming more difficult to obtain. Complete vessels are next to impossible to find. The majority come broken and glued, or in pieces ready for you to assemble, commonly referred to as “sack pots.” Sack pots are my personal favorite, but I’m a glutton for punishment. If you have a bit of free time on your hands and don’t mind some hair-tugging frustration, then I think you’ll love them also. They are the ultimate ancient 3D jigsaw puzzle. Complete bowls can be incredibly expensive and sometimes sack pots are the only viable alternative. Most items are much more eye appealing as well as valuable restored, than in their former broken state.

Restoration has been practiced for a very long time, commercially and for the hobbyist. It seems that for any item of antiquity that can be broken, battered, or abused, there’s someone out there who can fix it—furniture, vehicles, guns, arrowheads, pottery, your grandpa’s toupee. Some professional restoration can lead into big bucks, and if you’re as cheap as I am, the budget won’t allow it. With this guide, I’m going to attempt to give you a better understanding of what goes into the pottery restoration process, and give you the confidence to try it for yourselves.

Items Required:

Durham’s Rock Hard Water Putty (available at hardware store or lumberyard)

Acrylic Paints (no neon colors, only flat “earthy” colors)

Knife or carving tools (X-acto works well) Paper Towels

Sandpaper

Water Soluble Glue (superglue isn’t water soluble, use Elmer’s or similar)

Paintbrush (medium and small)

Masking tape

Sack Pot Preparation & Assembly

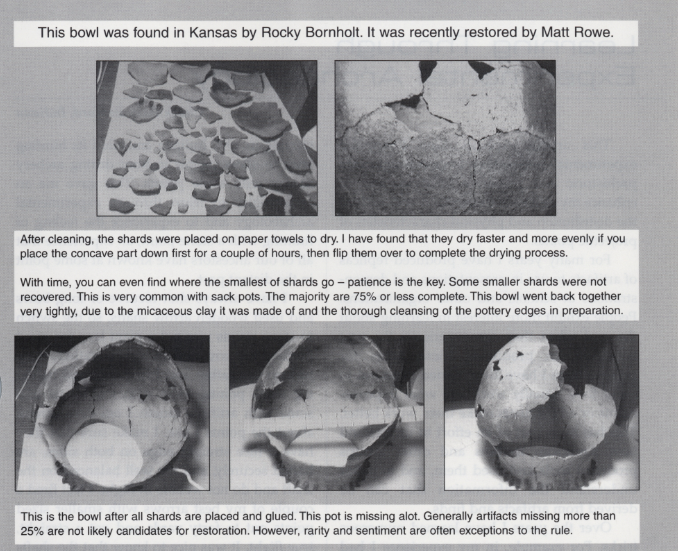

WASH ALL PIECES — A light rinsing will work on most pottery, but every now and then you’ll run into pieces that really have some caked up crud. Find a large container, fill it with water and then put your pottery shards in. Very gently clean both faces of the shards by rubbing lightly with your fingers. Do not get carried away in the cleaning process, or force removal of deposits, as this could risk damaging the pottery. I recommend doing all of this from a large plastic container. If doing it from sink and running water, you risk small pieces breaking loose and losing them forever. Aboriginal painted vessels are oil based, so this method also works for me with no adverse affects, ‘knocking on simulated wood.’ Edge treatment is the most important part of the cleaning process, to insure a tight fit when gluing. I have found that a soft bristled toothbrush will remove the dirt from the nooks and crannies of the edges, without being overly aggressive. Once all pieces have been thoroughly cleaned, lay them aside on paper towels to air dry.

Assembly

It is best to start out with the bottom pieces of the bowl, or you’ll undoubtedly end up “painting yourself into a corner.” First off, put down the glue. You heard me, put it down…no, seriously, put it down. I know you’re anxious to play with it, but you’ll just end up gluing your finger to your ear, so put it down. You need to have a general idea of where most pieces go before you attempt to semi-permanently attach them. This is where masking tape comes in. You can use masking tape to sort of loosely hold shards together while you figure out where they all go. Start off by finding bottom pieces that will allow any other shards to fit into them from any direction. Watching the bowl take form is the most time consuming and rewarding process.

Once you have taped together the shards and are confident that you are ready to attach them more permanently, remove tape and arrange the pieces in order on paper towels. If there are numerous shards, it may be easier for you to attach a small piece of tape to each one, numbering them individually, so you can remember their location. OK, now you can pick up the glue. Again, starting with the bottom pieces, start assembly. A thin line of glue in the center of the pottery edge is preferred. Excess glue is unsightly, so don’t get carried away with it. The less glue, the better, if any squeezes out of the seams, then you are using too much. Rock the piece you are gluing back and forth to seat it firmly, you want as tight a fit as possible. Be sure shards are in alignment before you let them dry, the slightest flaw will affect the overall appearance.

Helpful Tips

1. When dealing with super small pieces, it’s sometimes better to squeeze out glue in a small container, and apply it with Q-tip or small paintbrush.

2. NEVER glue together shards in which you will have to insert a smaller piece into later.

3. Do not attempt pottery assembly under the influence of alcohol or drugs, your olla could end up looking like a ladle.

Restoration

OK, so you’ve assembled your first vessel, congrats! Now you have a choice of leaving it as broken and glued, or to further it by patching the cracks and holes. There are different degrees of restoration. Some are simply patched, the holes filled without paint added. This gives a nice semblance of completion to the vessel, without “covering up” the patchwork. Others take it a step further and match the natural look, making it very difficult to tell that restoration has ever been done. It is simply a matter of personal choice.

Patching

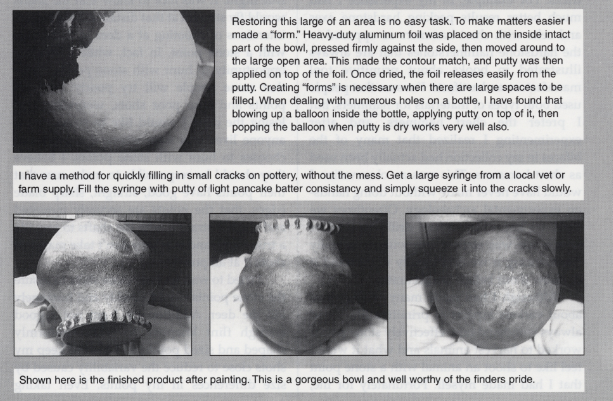

Plaster of Paris, bondo, spackling compound, just about anything you can think of has been used for pottery restoration. I prefer to use Durham’s Rock Hard Water Putty. It is cheap, fast, sets up hard, doesn’t shrink, and carves with ease. Find a disposable container lying around and dump about half a cup of the powdery Durham’s in it. Stir and mix in water until it becomes about the consistency of a thick pancake batter. The mixture will be light tan. Powder tempera paint can be added if a darker base color is desired, but go lightly, too much can affect the hardening process. Remember to work somewhat quickly, as the mixture sets up in just a few minutes. Using your fingers, apply the mixture to the areas to be filled. For cracks, use minimal amounts at a time, squeezing it into the seams and smoothing as you go. It is better to leave just a little above the surface of the pottery, than below. Durham’s doesn’t shrink, and the excess is easily carved off. For larger areas or holes, press the putty firmly against the broken inside edges first so it will adhere better. Build up the area slowly, until the holes are completely filled. It will stiffen up in just a few minutes, but more mixture can be made quickly if necessary.

Carving

Durham’s reaches peak hardness in about 8-10 hours. The first hour is the best time to do your main form rendering. A curved blade knife works well for initial sculpting. Using the flat blade, scrape the putty off, matching the contour of the bowl. Be sure not to scrape away too much and go below the surface level of the pottery. More mixture can be quickly made if need be, to fix air bubbles, or any mistakes. In the event that the bowl is corrugated or textured, go by the outermost part of the pottery (you can apply texture when the mixture has fully cured). Lightly sand the restored area to bring down any rough edges and contour the piece until you’re content with its overall shape. This also is the best time to clean up any excess putty that may have gotten over onto the original surface of the vessel. Take a glass of water, dip a soft bristled toothbrush in it, and gently clean up the residue on the sides of the patchwork. A soft rag or paper towel will also work, if toothbrush is not handy. Let the water do most of the cleanup work, do NOT scrub forcefully. After you are satisfied with the initial form, set aside to finish drying.

Texture

No ancient earthenware vessel is completely smooth, none I’ve seen at least. If you look really close, you will notice scratches, exfoliation, dips, grit, tooling marks, etc. It is sometimes tough to duplicate these micro-flaws, but it can be done. You can match corrugations, filleted rims, incising, noded rims, or just about any method used by the ancients. My favorite item to use for carving/texturing is an X-acto knife kit, available at a Wal-Mart near you. A lighted magnifying glass (I use 10x desk mount) comes in handy when examining the pottery to match textures. If there are numerous dips or scratches on the original pottery, you want to make sure to add some on the patched spots. Most pottery has very small pits giving it a gritty surface. This can be recreated simply by repeatedly jabbing a needle or sharp tipped implement into the putty. For more extreme surfaces you can use a vibratory engraver with good results. For scratches, simply rake a sharp instrument across the surface. Go crazy, there are no rules! I have found that “popouts” can be made by inserting a sharp tipped knife, then flicking upwards, breaking out tiny amounts from the surface at a time. You don’t want the restored area to look too smooth and crisp. Tmy flaws give character and every aboriginal artifact has them. There are many ways to help hide detection of your restoration. The trick is to draw somebody’s eye away from seams and make them focus on something else. My favorite method is to put an obvious flaw (popouts work nicely) in a very noticeable location. Have fun with it; imagination is your only limit.

Painting

Painting is probably the hardest part of the restoration process to master. Before you ever pick up the paintbrush, you’ll want to examine the vessel very closely. You will notice that there are many shades and colors, but one dominant hue overall. This is what you want to focus on, the base color. Since it is much easier to darken, than to bring back lighter, you want to apply the lightest base tone first. Squeeze out small amounts of acrylic paint onto a pallet. Primary colors are all you need if you don’t mind mixing. I’m lazy and like to save time by buying many different hues of earth tone colors. Once you have acquired your base color, dilute it heavily with water. To prevent streaking, layer the paint in watered down doses. Apply paint at the sides of the restored area and work inward, making sure you don’t get any paint on the original pottery surface. I prefer to use a small paintbrush for the delicate edgework, and then a larger brush for the central areas. You may experiment with Q-tips, I have heard this works well for some people.

Once your base color has been applied and you are content with the results, focus on larger stained or shaded areas. A cotton ball works great for dabbing on soft colors or matching the dark “fireclouds.” As in texturing, let your imagination flow in the painting process. Once the general color has been matched, you can focus on the smaller, more tedious work. You can fake shell tempering with a large stiff bristled brush and off-white paint. Push the brush into the off-white paint, and then thrust it repeatedly into a paper towel, leaving very little paint left on the brush. Dab the end of the brush lightly onto the restored area of the pot; practice until you get the desired results. Acrylic paints are water based and very forgiving. A wet paper towel will get rid of mistakes, so have fun with it.