by E.J. Neiburger, Waukegan, Illinois

Originally Published in the Central States Archaeological Journal, Vol.57, No.3, pg.152

Above: Figure 1 Bundle burials from the Late Woodland period.Lake County, Illinois

The remains of a people tell a story. Their writings and art tell what and how they thought, what they treasured and what they feared. Their garbage gives us clues into what they ate, discarded and distained. Their graves, bones and artifacts tell a story of what was valuable, how they lived and how their bodies reacted to the life, genetics and environment of the times. Since we share the same world (more or less) as the people who lived here before us, archaeology gives an excellent opportunity for us to study our ancestors and the environment we continue to share. Though our ancestors may be of a different race or races from what we are today, a human is a human and whether our recent ancestors came from the Old World or New World, we live here now and are affected by similar climates, environmental conditions (trace elements in the earth, water flow, seasons, natural contamination such as radon, fungi, etc.) and nature as a whole; just like our Indian forefathers.

The Woodland period in the central US existed from 1000 BCE to 1000 CE. It is divided into three sub periods: the Early Woodland (1000 BCE-10E) where the Archaic period (8000 BCE-1000 BCE) Indians began to farm, have settled villages, use the bow and arrow and make pottery. The Middle Woodland (1 CE-500 CE), as typified by the Hopewell culture, advanced farming with the “three sisters” (corn, beans, squash), developed sophisticated and extensive trade, produced elaborate art work, metal technology (including some copper casting), cities, complex burial mounds and customs with many grave goods and a rich, political-religious hierarchy involving a stratified society (rulers, priests, commoners). The Late Woodland period lasted from 500 CE to 1000 CE where the social systems, large settlements and large populations gradually disappeared or reverted to the lower, less organized level of civilization typical of Early Woodland peoples. This was due, in part, to unfavorable climate change. Complex society began to rise again with the Mississippians (1000-1500 CE). This rise and fall of civilizations makes an interesting study.

The Woodland Indians occupied vast territories and the above mentioned aspects of Woodland culture was not homogeneous. Some areas exhibited advanced technology (e.g. copper smithing, cities) while, at the same time, other places were comparatively primitive. Some locals systematically farmed while others remained as unsophisticated hunter-gatherers. Because of this mix, the Woodland period had a broad range of customs and technology (some advanced, some primitive) which affected the health and well being of the population region by region. We have the same situation today with many people living in first world, modern cities with adequate (or too much) food and medical care while others eek out a basic existence in small rural farms or slums without adequate food, electricity or antibiotics. Though there are differences, one can make some fairly accurate interpretations of who the “typical” Woodland people were, how well they lived and how healthy they were.

HOW DO WE KNOW

We have the remains of a prehistoric civilization which did not have any writing unlike its Old World contemporaries (Mesopotamia, Greece, Rome, etc.). Many camp and village sites have been excavated along with the art, tools, debris, post holes (dwellings), refuse and other informative relics. Remains of animal bones, seeds, pollen and shells tell us what and how much the Woodland peoples ate, what and how much they hunted and what they grew or harvested. Oral traditions from existing or historic tribes and reports of early explorers (e.g. Jesuit Relations 1600s) give us hints as to the daily lives of these folk. Artifacts of tools, weapons, jewelry along with occasionally preserved wood (tree ring data), cloth and furs of that period help us understand the lives of the Woodland Indians Graves, their location and contents provide the demographics of these natives. This is important data on their populations, their social order (e.g. exotic graves of chiefs vs the simple graves of commoners), wealth (grave goods), disasters, population ages, sex ratios and life tables. Examination of the skeletons and their DNA, though not complete, provide us with information about aging, work loads, diseases, injury, nutrition, race and longevity. Though we do not know the full story, analysis of this data gives some excellent data to base our understanding of Woodland life.

Not only do we have reports from early explorers, we have studies of modern physicians, anthropologists and sociologists who have visited and studied historic and existing tribal groups (e.g. Chichimec Indians) who are genetically close and live similar lives as did the Woodland Indians. Some of this data can be extrapolated to recreate life of the 100 BCE era.

Above: Figure 2. Normal (top) and fractured (bottom) tibia (lower leg) bones. The fractured bone was not set and healed poorly creating permanent disability.

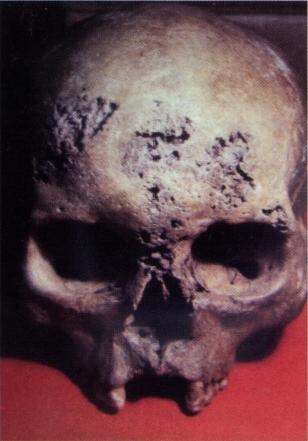

Above: Figure 3. Late Woodland skull from Spencer Lake Wisconsin. Note the axe (tomahawk) and knife wounds (scalping).

THE HEALTH OF THE WOODLAND PEOPLE

In recent times there has been a romantic movement which has colored thought about the kind of lives ancient natives lead. Many of these theories were Rousseauian emphasizing the “noble savage” living in domestic peace, in perfect balance with nature in a Garden-of-Eden like forest. The theory was fond of drawing an inference to perhaps modern man emulating this life style, shrugging off the shackles and ills of industrialization and thus living happily ever after as the Great Spirit intended. The scientific record is just the opposite. Life in Woodland times was short, brutish, sickly and relatively miserable in an environment of dwindling resources. Compared to modern times in our present society, the Woodland people lived miserably. One must keep in mind that at that time, Woodland life was not that much different from that of the Chinese peasant, Roman tenement dweller or the Gallic farmer toiling the fields in the Old World. With the exception of the “upper crust”, everyone lived miserably.

Analysis of thousands of skeletons of Woodland people show a short statured population who stood 148 to 181 cm (54″- 67″) tall. The males were significantly taller (ay.164 cm) than the females (ay. 150cm) Average weight was 59 kilos (130 lbs) with males out weighing the females by 10%. The people were small, lean and wiry. Most worked in the fields growing corn, squash or beans. Some of the larger individuals were warriors ( display more injuries, buried with weapons) or chiefs/ shaman and their families which composed the upper classes. Like today, the upper classes generally ate better, grew better, lived longer and were buried/ cremated with more wealth.

Population density was moderate. In one Illinois study of Middle Woodland populations, 5300 individuals were estimated to inhabit 11,000 square miles of territory thus creating a population density of one person every 2 square miles. Except for the large villages/cities, the environment was not terribly crowded by today’s standards. Unfortunately, such a population density was still too intensive for hunting of animals (e.g. deer) who became scarce. This is evidenced by the meager number of animal remains found in village garbage pits. Animals, with the exception of clams and fish, were an occasional dietary treat, not a staple though this varied from local to local.

Figure 4. Two vertebrae from a Woodland Wisconsin Indian. The right vertebra is solid (normal) but exhibits severe arthritic “lipping” (saw tooth formation) along the edge. The left vertebra was hollowed out by pressure from some type of soft tissue lesion (e.g. cancer).

Figure 5. Fractured tooth and abscess cavity (below the tooth) of a Late Woodland Indian from Lake County, Illinois.

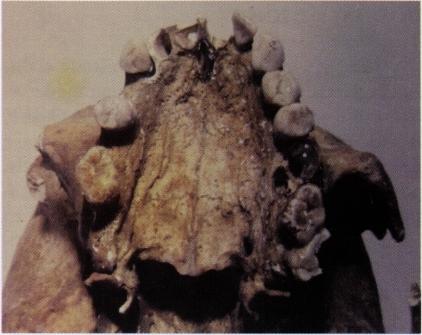

Figure 6. Upper jaw from the Kratz Creek, Wisconsin site showing extensive dental decay, periodontal disease and dental abscesses.

The many burials presented a fairly interesting set of life tables. Males and females were found in equal numbers ( fig!). The average Woodland man, surviving childhood, lived to 27 years of age. The women lived to 25 years. The typical Woodland community lost 30% of its population between the ages of 1 and 10 years of age, 10% died between the ages of 10 and 20 years. 30% died between 20 and 30 years, 24% died between the ages of 30 and 40 years. Only 6% of the population survived beyond the age of 40 years. Old people were very rare. One can say that the Woodland people were a youth centered culture in which most people died in their childhood. Women had babies early, died at a greater rate and earlier than men (probably due to pregnancy complications) and showed evidence (muscle scars on bone, arthritis) of considerable hard work. Probably more children died than was reflected in the above grave data. In many situations, the bones of young children, being small, weak and fragile did not get buried or were lost to the erosive nature of the Midwestern soils, cremation and reburial (bundle) customs. In a recent study of the primitive Chichimec Indians of the southwest US-Mexico (1946-1955), 67% of the population died within the first 3 years of life. I suspect the Woodland people had similar statistics and lost considerably more infants than there was estimated from the graves and cemeteries. A high birth rate made up for this loss so one can assume that women spent considerable time in pregnancy with its accompanying hazards.

Skeletal remains only identify a small fraction (5%) of the diseases suffered by the Woodland people. Broken bones, anemia or bone cancer leaves telling skeletal lesions( fig 1-12). Rarely does one find the marks of Tuberculosis, diabetes, syphilis (yaws), sepsis, flu, typhoid fever, malaria or other killer diseases of the time in the ancient skeletons (Fig 9). Most disease is soft tissue born and leaves no marks or evidence on bone except in rare cases (e.g. mummies). The big killers of the Woodland period, as well as the third world today, were: pneumonia, dysentery, fevers, starvation and soft tissue infections which leave essentially no skeletal traces. Like most people in pre-antibiotic days, the major deaths involved over-work, parasites and poor nutrition contributing to a lowered host resistance. This state encouraged garden variety diseases/infections to become quickly fatal. Diarrhea’ diseases probably killed most children. Pneumonia, food poisonings, injuries and gastrointestinal diseases killed the adults. Malaria and typhoid fever were probably endemic in the population, as they were with early European settlers and still are today, but no evidence remains. As was with all large populations, epidemics came and went leaving no record.

Figure 7.Trephination of a skull from Milwaukee County, Wisconsin. Notice the perfectly round hole without smoothing of the bone (healing). This individual died around the time of the operation.

There were numerous fractures and bone injuries found in the Woodland skeletons (fig2,3,9). Most Woodland sites had skeletons with a 20% to 47% rate of healed bone fractures, especially in the face and limb bones. 2% experienced projectile injuries (e.g. arrow points in bone)( fig 13), Soft tissue injuries such as a spear in the abdomen left no records. Up to 18 % of skeletons showed skull fractures, most probably from warfare, domestic disputes or falls (fig 3). 3% had visible bone infections (fig 9). There was cannibalism. (Fig8) The Midwest was a rough neighborhood to live in.

Figure 8. Long bones from a Late Woodland site in western Wisconsin. The ends of the bones were broken open to extract the marrow; a sign of cannibalism. The femur on the bottom of the frame is significantly bowed/curved which is a classic sign of Ricketts, vitamin D deficiency.

Most adults showed extensive dental wear from a coarse, gritty diet (fig 5 & 6). 15% had dental decay, 16-25% had severe dental abscesses caused by decay, broken teeth or gum infections. 40% of the skulls examined showed severe periodontal disease. Just about everyone in Woodland times had dental pain. Hypoplastic marks on teeth identify illness or poor nutrition. It was frequent. These markings plus skull bone porosity (criba orbitalis area-anemia) show the Woodland people were under nutritional stress. Since the Woodland people had relatively short lives, many of the diseases we see in the elderly of today were of little problem. The Woodland people probably did not live long enough to develop the chronic cardiovascular disease or cancer which abounds in our older citizens of today. Observed tumors in skeletons (bone lesions) was less than 0.05% but cancer occasionally did occur (fig 4,5,10).

What the Woodland people had in abundance was osteoarthritis(fig 4). This form of wear and tear arthritis causes bony growths (lipping) to form on the degenerating cartilage ends of long bones and vertebrae. It is quite debilitating and painful and was caused by excessive work (heavy loads), bending and trauma. The Woodland Indians worked hard and wore out quickly. We have little evidence of infectious diseases since most of these conditions leave no marks on the bones. There are some reported cases of syphilis-yaws (facial bone defects) and tuberculosis (vertebrae collapse) but not many(fig 9,10). Ancient coprolites (fecal deposits) and other remains show eggs of parasites, especially tape worms, amoebae, flukes and nematodes. Woodland life was not too clean by our standards.

Medical care was minimal. Local plants such as snakeroot, wild plum, and cannabis where probably used by local healers as they were during historic times (e.g. 1650 CE). There is some good evidence of deliberately set bones which healed well…or poorly (fig 2). There are some cases of trephination surgery, the deliberate opening of the skull to relieve hematoma pressure ( Fig 7). Other than this, medicine probably consisted of herbs, prayers, rituals and hand holding.

Figure 9. Early Woodland Indian skull showing extensive lytic forehead lesions consistent with yaws or syphilis.

The Woodland Indians appear to be a hard working, industrious people beset with sickly, short lives, the trauma and loss of numerous children, violence and a variable but limited food supply. They created wonderful art (e.g. Hopewell), a monumental society and new discoveries(e.g. corn) that still sustain millions of people today. It is unfortunate that no written record exists for if it did, the Middle Woodland peoples would probably stand with the ancient Maya, Inca, Mesopotamians, Egyptians and other great nations that led man out of the Stone Age.

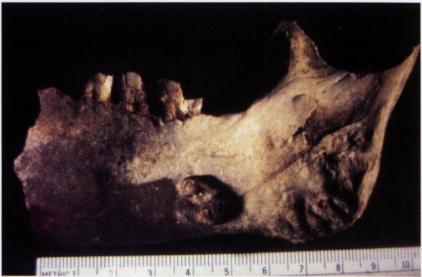

Figure 10. Lower jaw from Dodge Co. Wlisconsin with a deep central cavity caused by oral cancer.

LIMITS

There is a fine line between what we see in the ancient remains of the Woodland people and what we can tell happened to them. Often diseases of the past can mimic different diseases of the present. Historic diseases like the “plague of Athens”, quinsey, augh, and “pox” are extinct or unknown and can only be theorized as to what their origins really were. New diseases are constantly appearing (officially one a year), old ones fading. Counting skeletons in a cemetery may not give an accurate view of a population that may have cremated and scattered the remains of captives, slaves or the underclass. We have some hints but the level of certainty is not based on hard, complete data. It takes thousands of skeletons to get an accurate sampling. As time goes on, more and more data will be collected, analyzed and tested using new tools and broader thought. More should be learned and what we know, refined for a better picture of the past.

Why do we need to know? Why should we study old bones and artifacts? Why disturb the dead? Not only is it for some egocentric, voyeuristic need to know how the ancient people lived, relative to us, but for our basic survival as individuals and as a culture. Diseases, especially viruses, come and go, mutate and hide and then may reappear over millennia. So do many other microbes. Did AIDS, Hanta virus or prior diseases exist in the past? When? Why did they develop and why did they disappear? Will they reappear as a new epidemic?

Our ancient skeletal material is a reservoir of information on how these diseases affected humans and under what circumstances. They present a history of the effects this environment had on humans and how it interacted with past diseases. The presence of specific trace minerals, bacteria, temperature and a wide variety of natural and manmade conditions (e.g. obesity, native medicines, exposure to sunlight) can affect our understanding and treatment of local diseases; maybe future epidemics. Each skeletal collection is unique to the local it was found. If a disease outbreak (e.g. hanta virus in the South West US) occurs in a particular local, the skeletal collections in that area become critical in understanding and fighting the sickness as compared to an unrelated collection in some other part of the country.

Figure 11. Patient with oral cancer similar to figure 10, causing a hard swelling of the lower jaw and neck. Diagnosis was made too late; Fatal.

EXAMPLES OF HOW KNOWLEDGE OF ANCIENT DISEASE FROM BURIALS HAVE SAVED LIVES TODAY.

The Native American people as a group suffer significantly more from a number of diseases as do the general US population. Indians living in the US have 638% higher alcoholism rates, 400% higher TB rates, 291 percent higher diabetes rates, 91% greater suicide rates, 67% greater pneumonia/ flu rates, 38% greater gastrointestinal disease rates, 20% greater heart disease and 14% greater cerebro vascular disease rates than the general population. Northern plains Indians have high lung and colon cancer rates. Most other Indian people have lower cancer and HIV disease rates than the other US groups. It is not all genetic.

For example, the diabetes problem is killing more Indian people than all of history’s guns and bullets. We have, using ancient skeletal material, already discovered that this disease was seldom present in the Woodland people and other ancient populations; most likely because of the minimal diet and low weight so common to people of that period. Because it was no problem for the ancient (e.g. Woodland), thin Indians and a big problem for today’s overweight Indian people, a greater focus on early diagnosis and reducing the high calorie diets of modern day Native Americans (e.g. in schools) is now the prime treatment for this debilitating disease. In 2001 diabetes rates were 291% greater than the general US population. Because of the above focus, in 2003 the rate was 208%; an approximate one third reduction. Thousands of lives are being saved because of this research. The non-Indian populations have also learned from this lesson. How many of us have been told by our doctors to lose weight and cut carbohydrates?

Figure 12. Central Illinois Woodland Indian with an arrow point lodged in his temple. The wound entered the brain and was fatal.

Tuberculosis occurs in modern Indian people 400% more than in the general US population. Ancient skeletons show this disease was much less prevalent in Woodland times; even in large population centers. With this knowledge, treatment and prevention therapies are being developed that take into account, the weak genetic immune response to TB microbes that Indian folk seem to have as compared to other population groups who respond to different therapies. Up to this time, Indians were treated like everyone else; but they responded poorly as compared to other races.

A rare form of oral cancer was noted in many ancient skeletons (Fig 11 & 12). It eroded the jaws and eventually became fatal. With this knowledge, people of Indian ancestry can now be checked by their physicians and dentists for the early, treatable stages of this disease. If detected early, treatment is minor, survival is 99%. If not seen until symptoms appear, the disease is 99% fatal.

Though many more people, of all races, can be helped, political racists and religious fundamentalists are forcing the destruction of ancient skeletons such as the Woodland Indian collections in a misguided religious-political reburial movement. It is only with Indian collections. Skeletal collections and other races are treasured and do not have this problem.”Used by Permission of the Author”

To learn more about or to join the Central States Archaeological Society, click here:CSASI.org