by Matt Rowe, Curator, Museum of Native American History, Bentonville, Arkansas

Woodland points from the Museum’s collection. From left to right: A Dickson point made of heated Florence Chert, 4 inches in length .Norton Point found in Gasconade County, Missouri. 4 3/8 x 2 1h inches and made from heat treated Burlington Chert. A Snyders point made from a chert known as Jefferson City Varation II. It was found near the Spring River at Springfield, Missouri. It is 3 4/4 inches long. At far right a second Dickson point made of heated Burlington chat. It was found in Illinois and measures 3 11/16 inches in length.

Mounds found on the farm of General Mordecai Hopewell near Chillicothe, Ohio gave name to a civilization that thrived over 1500 years ago. The Hopewell Indians were known as superior craftsmen who created some of the finest works of art in the prehistoric Americas. They were a religious people and this was made evident in their artifacts that contained symbolisms of mythical people and beasts. Many people consider this society to be the epitome of the Woodland time period, with their great earthen work mounds and fine relics made of exotic materials. Even though their reign was spectacular, it was short lived. The Hopewell dominated only 500-600 years, from middle to late Woodland times.

Hopewell Indians established villages along waterways, which they would navigate as part of a very extensive trade network. These trade routes were used to attain raw materials such as copper, shells, mica, gem quality stones, and other exotic goods. They were well traveled, and it’s not uncommon to find items on a Hopewell site made from materials from hundreds of miles away. Burials in Ohio and the east have contained marine seashells, copper from Wisconsin and even large blades made of obsidian that was sourced to Yellowstone, in Wyoming.

It’s hard to call the Hopewell just one group of people. More accurately, it is comprised of many different groups that flourished in small communities throughout much of the United States, from New York well into the central states of Kansas and Oklahoma. They covered a very large area that is commonly referred to as the “Hopewell Interaction Sphere”.

While many studies have been done on the eastern Hopewell areas of Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, surprisingly little is still known about the western fringes. One thing is for certain though; there are contrasting differences throughout the reach of these people. The great effigy mounds and ceremonial centers are largely absent in the Ozarks and graves are usually small and without fanfare. The villages are small and agriculture was relied upon heavily.

Exotic raw materials weren’t utilized as frequently in the western region, but you will find them every now and then. I know of three cores and several spalls made of obsidian found in Mayes County, Oklahoma, all from the same Hopewell site. Don Arthurs of Salina, OK, found one of the cores and I found the other two. Reed Springs, Jefferson City and other localized cherts were used to some degree, but the lighter Burlington and Keokuk seem to be the most preferred. The vast majority of these cherts were heat altered prior to knapping, even though some knap very well without it.

One intriguing tool that appears unique to the Ozarks area is simply known as a “Hopewell Pick”. The picks are generally 6 inches or longer and can weigh up to a pound. They are crudely made by knapping a long bit into a nodule, leaving the cortex on the other end to act as a handle. The end result leaves them looking like a slender Kerrville knife, or monstrous drill. They are found commonly in agricultural areas on Hopewell sites.

Hardstone pipes, gorgets, dolls, celts and other-pecked & ground tools are found to be more abundant in Illinois, Indiana and eastward. The platform pipes and large effigy “Great Pipes” are largely non-existent west of the Mississippi. One reason for this could be the diminutive resources for hardstone material available to these western groups. Ozark natives were often convinced to make adornment and tools out of rougher materials such as sandstone, shale and even the anomalous “Cotton Rock”. Celts made of cotton rock are very lightweight, fracture easily and don’t seem like they could ever have served much purpose. However, the material wasn’t always so fragile and volatile. It’s the direct result of tripolitic weathering, completely changing the molecular structure of the stone. In the Ozarks area, cotton rock seems to primarily occur in material from the Reed Springs formation.

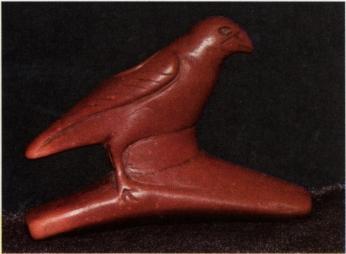

Above: Known as the “McAdam’s bird effigy pipe., this Hopewell Platform Effigy Pipe was found in the mid 1800’s in Madison County, Illinois. It is made of red Illiniois pipestone. It is likely that it had freshwater pearl inset eyes at one time.

The Snyders point cluster also shows many variances throughout its distribution range, although the Snyders point itself remained much the same. The Grand point in eastern Oklahoma appears to be the lateral equivalent of the Gibson point of Illinois and is probably the most commonly found throughout the Ozarks. There have been a few rare examples of beveling, basal grinding, burination and even light serrations found on Snyders Affinis points in Oklahoma, Missouri and Arkansas, but I have seen no reports of it elsewhere. The North blade is another type that was utilized throughout the range of these woodland Indians. Contrary to popular opinion, the North is indeed a knife, and not a preform. The term preform denotes that they have yet to be finished and utilized, yet North knives exhibit wear patterns and resharpening that is consistent with them being used as a hand-held knife. The confusion lays in the fact that the preform for the Snyders would look pretty much identical to the North and would be indistinguishable unless wear or resharpening was evident.

There’s little doubt that these Hopewell Indians are the descendants of the Adena culture. Contracting stemmed points like the Dickson are strong evidence to help support this. The Dickson and Waubesa were morphed from the earlier Adena Stemmed points, but are in fact Hopewell. The Hopewell crafted many tools that are often mistakenly identified as belonging to another culture or Indians from another time. They utilized finely crafted gravers, unifacial blades and square knives very similar to the Paleo-Indians. They also practiced core technology, burination and made tools with parallel flaking that Paleo-Indians were long thought to have a monopoly on. It’s common to see their tools attributed to another culture, both older and newer.

This pipe is known as the Eiker “Flying Eagle” great pipe. It was found in Ross County Ohio.

A Wood duck effigy great pipe. Found in Ohio.

The ceramic vessels created by the Hopewell are ornate and delicate. Intricate designs were carefully impressed into the wet clay of these vessels using carved stamps, combs and shells. It’s been a lifetime goal of mine to find one of these complete, but I think I stand a greater chance of finding a cache of Clovis points.

Whether it be to the east or west, the Hopewell were an elaborate people who possessed a high degree of technical development. The artifacts that they left behind are some of the finest ever created in North America.